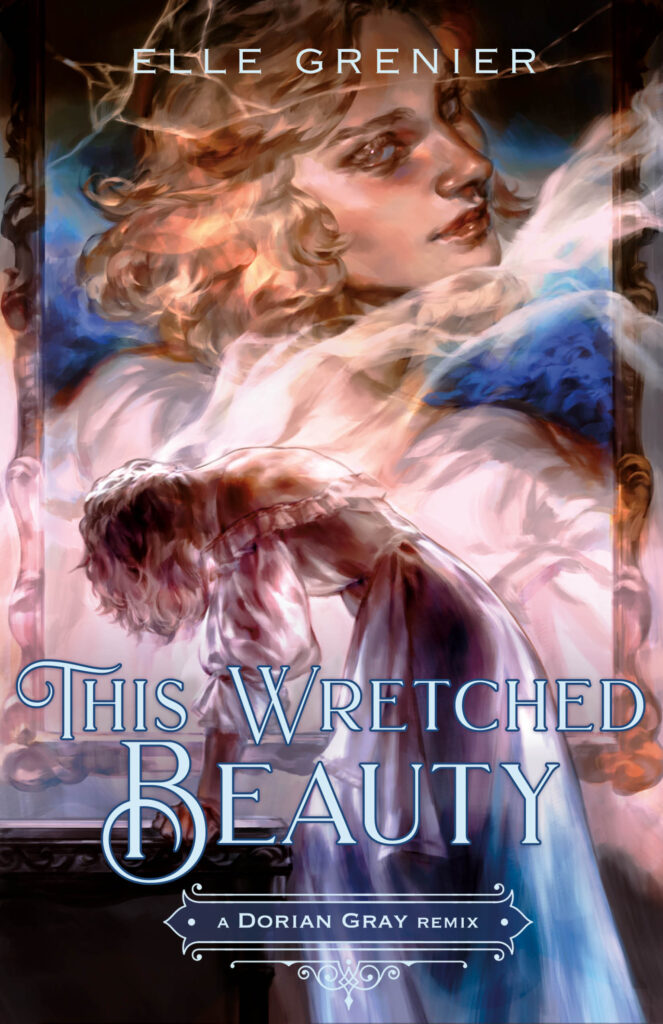

Elle Grenier is a queer and trans author from Southern Ontario currently residing in British Columbia with her partner and their three cats. Elle has a BA in English Literature from the University of Toronto, and their debut novel, This Wretched Beauty (A Dorian Gray Remix), is being published as part of Feiwel and Friends’ REMIXED CLASSICS collection.

This Wretched Beauty is a transfeminine YA retelling of The Picture of Dorian Gray, set in 1860s London with a richly gothic atmosphere. What inspired you to remix Oscar Wilde’s classic through this specific historical and queer lens, and how did you approach making the story your own?

I’ve felt a connection with The Picture of Dorian Gray since the first time I read it near the end of my senior year. Between the generally gloomy tone of queer representation in mainstream media and the generation of elders devastated by the AIDS crisis, there weren’t many ways to imagine what it would look like to get old as a queer person. It was easy to fixate onto the idea of being forever young and passingly tragic—and that’s before even touching on the layer of dissonance added by my attempts at navigating my relationship with gender. Add in the fact that I then jumped into studying Victorian, queer, and gothic horror fiction, and I found myself picking up Dorian Gray more times than I could count.

I think the first step in retelling a classic like The Picture of Dorian Gray is to start with a point of friction, and for me that’s Dorian as a character. For all the love I have for it, the original novel strikes me as being more about Wotton and his fascination with the impact of his influence on Dorian, and it bothers me how much it romanticizes Dorian as a figure without exploring his inner life. That frustration became the question at the heart of This Wretched Beauty: what impact does it have on a person to grow up isolated, dehumanized, and objectified before they’ve even had the chance to understand who they are?

Your version of Dorian Gray steps into underground molly houses and drag spaces as well as elite society. How did you research or imagine this world — and what role does queer culture and expression play in shaping Dorian’s journey of identity and self-discovery?

I got more familiar with Victorian England in university, where I studied English Lit and pretty quickly funnelled into all things Victorian, gothic, and gay. My understanding of the era is a fun mix of the facts I’ve picked up between more pointed research and more general exposure, blended with the way the artists of the time liked to portray it. As for the role of molly houses and drag spaces in Dorian’s journey: drag and its many historical ancestors are all about stepping outside established lines to push those boundaries, much like queer culture in general. I can’t think of anything more central to discovery than exploration, and no better tool for that than a space dedicated to that very freedom.

The portrait in your story literally reflects the changes in Dorian’s life and choices. How did you balance the supernatural elements of the portrait’s transformation with the emotional and psychological evolution of your protagonist?

One of my favourite things about gothic fiction is that the emotional, psychological, and supernatural go hand in hand. They’re reflections of one another telling the story along multiple axes. To me, the most important part of balancing all three is to make sure the relationship between them is clear and the rules are consistent, and to trust your audience. I don’t think readers need to know why the portrait changes so much as how. Do the portrait’s changes build on each other in a way that makes sense? Do the changes feel intuitive to Dorian’s mental state and circumstances? If so, I think that’s all the reader needs to know.

Remixing a beloved classic carries the challenge of honoring the original while creating something new. What were the hardest parts (and the most rewarding parts) of reimagining such an influential story — especially around themes of beauty, self-portraiture, guilt, and reputation?

To me the hardest part of reimagining a story as influential as The Picture of Dorian Gray is respecting not only the novel but the history it’s taken on as a symbol for the ongoing censorship of queer art. Queer history, much like the history of marginalized peoples more generally, is a story of survival often written at the sites of trauma. Engaging with that legacy means making space for those points of trauma, but also finding glimmers of hope to help understand how we’ve survived what we have—and, by extension, how we can survive what’s ahead.

One of the characters in This Wretched Beauty, for example, is actually inspired by the historical figure of Ernest/Stella Boulton, who was publicly tried for sodomy after cross-dressing in public with friend and costar Frederick/Fanny Park. The case was ultimately dismissed due to a lack of testimonial evidence, especially after the deathbed testimony of Boulton’s lover, who insisted nothing had happened between them, and both actually ended up continuing their performing careers separately. Studying cases like this helped understand how questions of beauty and reputation weren’t only thematic but actually material in queer history and key to people’s survival. Being able to discover those breadcrumbs and understand how queer communities survived across the 150 or so years since is one of the most rewarding parts of retelling Dorian Gray.

As a queer and trans author with a background in English literature and an active voice in YA fiction, how does This Wretched Beauty reflect your own experiences or viewpoints on gender, image, and self-acceptance — and what conversations do you hope it sparks among readers?

Writing is less about reflecting specific images or viewpoints to me than it is a way to explore specific questions. Part of the fun I found in writing This Wretched Beauty as historical fiction is the way that stripping away the language of identity we now have available actually helped me focus on the tensions, dynamics, and feelings that shape them. I describe myself as queer and trans, yes, but I also think of queerness and transness as actions I take in how I navigate the world. Focusing on how the characters in the book understand themselves rather than the language they might use to describe themselves helped me understand the rich sandbox through which we fashion our own images.

That being said, I’d love to leave you with some of the questions I asked myself going into the work of writing This Wretched Beauty. What does it mean to deprive queer youth of community at the time when most people fashion their sense of self? How do isolation and a lack of available language leave them vulnerable to dangers they haven’t learned to look out for? What does the path to self-acceptance look like without a space to get to know ourselves? And, on a more universal note, how do we learn to love ourselves despite having a front-row seat to our own worst shames and insecurities?

INTERVIEW: YA SH3LF