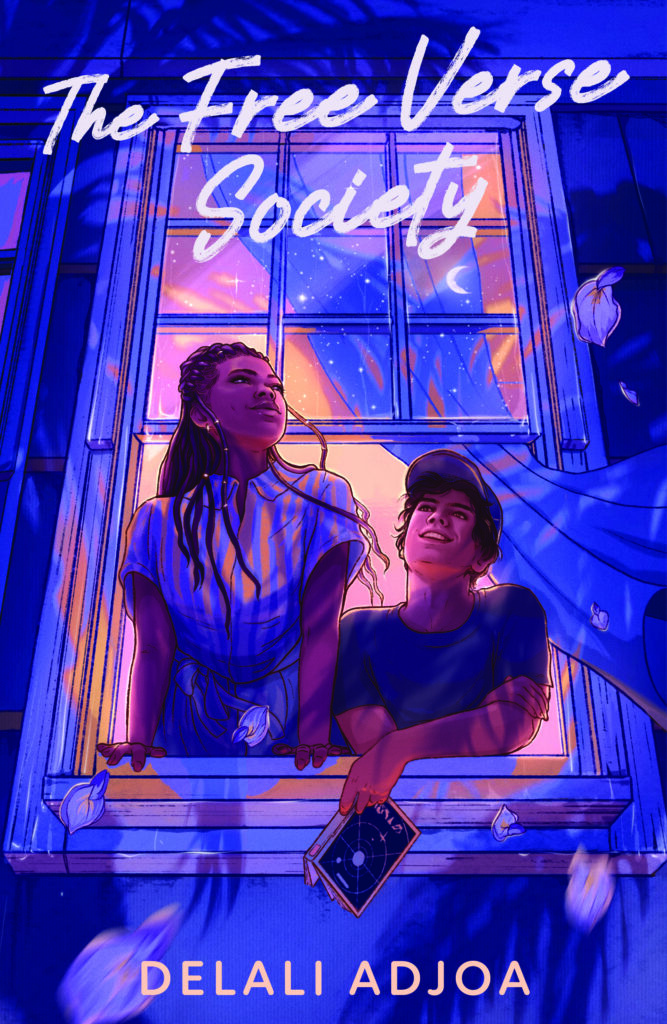

Delali Adjoa was born in Togo to Ghanaian parents but grew up in Canada where she traded sunny cottons for wool tuques and snowsuits. She has been chasing warmer weathers ever since. Delali writes fiction centered on identity, freedom, and family, and loves the American South for the stories it has buried. She is a graduate of the University of Kentucky and Georgetown University. Her debut novel is a YA Romance set to publish in 2026.

The book centres on Jae, a teen mom who placed her baby for adoption, and Derek, a student hiding the loss of his former life. How did you decide on these particular burdens for your protagonists, and what do you hope their journeys say about identity and second chances?

In writing these characters and their burdens, I was trying to answer a question: What do we do after loss, when what we love is no longer ours? Who do we become?

Derek’s story, although heavy, originated from a sunny trip to Delray Beach. It was the bright blue of everything–the sky, the water. I wanted to write a book set there. When I drove down A1A (or Ocean Boulevard), I imagined the inner lives of people who lived in those sprawling mansions and what it might be like to lose everything. I wouldn’t know until much later that one of the people living in those houses was Derek, but he was in my subconscious for a long time. Of course, the loss for him is more than financial; it’s the loss of his father, his mother (in her own way), and the loss of security in his friendships.

Jae’s story comes from meeting a teen mom when I was fourteen. We’d just moved to the US from Canada, and our new neighbor invited me over to meet her teen daughter. She was playing with a baby I assumed was her brother. He was her son. I wondered how their days unfolded, how she could raise a child when I couldn’t even figure out where to sit in the cafeteria. It made a deep impression on me, and when I came to write The Free Verse Society, I thought back to the teen mom I knew. This was before my own daughter was even a thought, so writing Jae’s story was an exploration of motherhood. I was answering my own curiosities, trying to understand how deep a bond with a child could be, and what it would feel like to have that bond severed.

In a sense, both Jae and Derek take their challenges as identities, so they come to believe that they cannot be loved if they are known. We’re more than the burdens we carry, and I think they inherently know this about others, but the story is a journey of them accepting that truth for themselves.

The setting of a high-school poetry club becomes a space for both refuge and reckoning. How did you conceive of the poetry club as a setting, and why did you feel it was the right environment for exploring themes of voice, healing and connection?

My high school experience informed a lot of this novel, including being a member of the poetry club. (Ours was called the Literary Magazine.) I couldn’t imagine a more impactful way to show Jae and Derek’s emotional growth than through their relationship to poetry and how they share it or keep it away from others.

With Jae in the beginning, we see her guarding her most intimate poems, afraid of revealing who she really is. And Derek goes from not understanding poetry at all to choosing it as a vessel for his deepest thoughts. It’s a growth that’s easy to represent on the page and felt natural to the story.

In your description you talk about “the power of the written word” tearing down walls these characters built around their hearts. What role does poetry play in the story, both thematically and structurally?

Derek joins the poetry club on punishment, so there’s naturally some resistance for him, and it allows for a positive character arc. Early in the story we see him seeking a new form of self-expression, but poetry feels too far from what he knows and is comfortable with. As he begins to face the truth of his life and who he is–and who he’s beginning to love–he finds the courage to be more honest in his poetry.

On the other hand, Jae gladly joins the poetry club, expecting it to be a study of famous poets, but instead, she’s called to share pieces of herself. She’s surrounded by people who don’t know who she is or who she’s been, and that’s frightening to her. So instead of sharing her deepest thoughts, she writes two poems, one that’s from her heart and one that’s essentially a decoy.

In the beginning, both Jae and Derek are afraid to be known, so their poetry can’t be what it’s meant to be. For the walls to fall around their hearts, they have to see themselves and see someone worth loving. They have to crack open their own hearts, pull out the spoils, and say, This heart is beautiful to me. That’s when they’re ready to love each other, and that’s when their poetry becomes real.

The book is described as a “hate-to-love” YA romance with strong “opposites-attract” dynamics between Jae and Derek. How did you negotiate the balance of romantic tension and the heavier personal issues so that both feel honest and compelling?

A lot of the romantic tension comes from the personal issues they’re dealing with but don’t tell each other. It’s the desire to hold someone close, but the fear of what they’ll see when you do. My editor was brilliant at finding small ways to make a big difference in tension, like letting Jae and Derek hang on to their secrets longer. So that’s why I think it feels both honest and compelling: the romantic tension that keeps us reading comes from the heavier traumas they’re hiding.

Your author bio mentions that you were born in Togo to Ghanaian parents, grew up in Canada, and write about identity, freedom and family. In what ways did your own cultural background or sense of migration/in-between-places influence this novel, particularly the themes of belonging, new beginnings, and hidden pasts?

I don’t think my migrant story makes me unique or particularly fascinating, but the inner conflict it creates is worth dissecting. It’s a common theme in my stories: being uprooted and transplanted into soil that doesn’t know you.

As a transplant, you’re neither here nor there. You might not look like the majority around you, but when you stand with the people you do look like, they don’t recognize you. When you speak. When you move. When you dress. You are your own thing.

My novel begins with Jae moving from Atlanta to Delray Beach, and in a way, it’s a revision of my own history of moving from Canada to the American South. Jae feeling so out of place she hides in the bathroom at lunch–that was me. It was me wondering how I could make my speech, my dress, my mannerisms fit. It was my shyness being misperceived, and not knowing how to begin my life again.

Writing the book was me reconciling with those painful new beginnings, of being the new girl with the new name, uprooted and transplanted.

Because the book deals with contemporary life, youth voice, and emotional stakes, what were some of the biggest challenges you faced in crafting this story? And on the flip side, what was the most rewarding moment during writing or revision of this novel?

I wanted to write an unputdownable book that was also introspective. That meant getting the pacing and romantic tension right. I achieved that, I think, for the most part, through many revisions, as one does.

I have two goals–that I can think of at the moment–in writing young adult. One is writing the truth beautifully, meaning talking about dark themes with honesty and hope and beautiful prose. The other is writing about teens in a way that adults can also enjoy, because we’re never too old to learn from each other. That means in scenes where there is immature behavior (which we all engage in from time to time), I wanted to get to the heart. The Halloween scene, for example, was written again and again until I found my own tears. That’s when I knew I’d found the heart. It’s revealing something deeper about the characters in moments when they appear anything but deep. That was probably one of my greater challenges, but I think it makes the book a moving experience for adults as well as teens.

As far as rewarding moments in revision, it’s when I see and feel everything so clearly it’s real to me. I already have a version of what happened written down, the ugly bones of it, but now it’s much more alive. This is often when I’m writing through high emotion, getting the words down as fast as I can because everything is happening right now, and I may never get the chance to record the truth of it again–it feels that real and that close. I write for those moments.

INTERVIEW: YA SH3LF