Alaa Al-Barkawi is a first-generation, Iraqi American Shia Muslim writer. She is the co-runner of QuillersSWANA, a literary organization dedicated to Southwest Asian and North African writers, and serves as a Literary Peace Ambassador for Threads of Peace. Alaa holds a master’s degree from Johns Hopkins University and has worked with refugee and immigrant students for nearly a decade. In the Country I Love is her debut novel.

Your novel centers on two Iraqi-American friends – one a seventeen-year-old single dad – navigating family expectations, faith, and a community crisis. How did you decide to tell this story through these particular characters, and what was the first concrete image or scene that made you know this story had to exist?

Because IN THE COUNTRY I LOVE is a story that explores identity and its relationship to social expectations, it felt fitting for this book to be about two teen Muslim boys: one trying to hold on to his faith, while the other has lost his connection to it. Those dynamics aren’t just internal feelings, but play out externally within their communities and the political climate they’re experiencing. Khaled and Yassir felt like the perfect characters to explore the spectrum of choice a lot of Muslims and Arabs face in Western societies, to either embrace or shy away from their identities that are being perceived as dangerous and threatening.

With that said, IN THE COUNTRY I LOVE has a backstory for its backstory. It took me a long time to be brave enough to write a story like this. I discovered writing when I was fifteen years old, and I never thought it was normal to write about people who had my identity: Iraqi, Arab, Muslim. Instead, I was writing similar characters from some of my favorite authors at the time (John Green, Stephen Chbosky): white teenage boys. Before Yassir and Khaled became who they are, they were two boys named Connor and Joey, one a teen father, and the other a golden boy with attitude. But there was something about the story that wasn’t quite working or clicking—by the time I returned to the book, I changed the characters’ ethnicities to match mine.

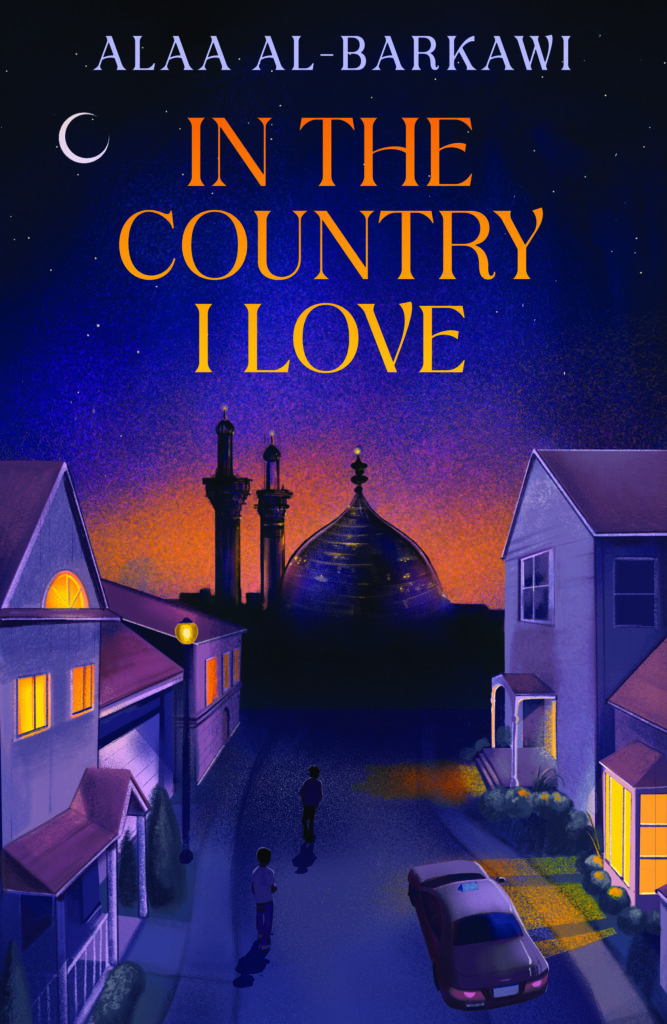

The first image that came to mind when restarting the book was the mosque, which at the time in my religious journey, was the last place I wanted to go and I knew for a fact the teen father whose faith had lapsed, hadn’t wanted to go there either. For me, the mosque felt too complicated and exposed too many internal doubts—yet, it was a place of familiarity, comfort, and unity. So, it felt natural for the story to start there, with the boys experiencing their Iraqi and Shia community in two unique ways. As my relationship with my faith returned to me, this story very much became a book about returning to faith, too.

In the Country I Love explores the Shia Muslim experience and intergenerational pressures in a SWANA community. How did your own background and your work with refugee and immigrant students shape the book’s emotional landscape and the way you depict community reaction to trauma?

At its heart, IN THE COUNTRY I LOVE explores the violence that lingers long after safety is promised. Real life inspires much of this book. Whether it be my life, people I know, or the realities my family had to face being displaced from Iraq and living in a refugee prison camp, before being resettled as refugees in America.

The boys’ families and their histories not only reflect my family’s displacement—but many Iraqi refugees who have endured decades of trauma. For many Iraqi diaspora kids, there is a gap between us and our parents’ generations, who had to survive a brutal dictatorship, multiple wars, and violent displacement. While our parents desperately wanted us to cling to their traditions and language, the US media was feeding us narratives that Iraqi and Muslim identities were detrimental to American freedom. As cliche as it sounds, I felt like I was stuck in two separate worlds. One moment I’d feel proud of my identity, and the next I’d feel like I wasn’t allowed to be myself if I wanted kids at school to like me. The less Iraqi and Muslim I was, the more I fit in. Yet, at some point, I couldn’t escape my identity, I don’t think any person of color living in a racialized world can, and this became a central theme in the book to explore because it very much shaped my coming of age story.

I embraced my identity when I worked with people who shared my background. Although I’ve worked with refugees and immigrants for nearly a decade, between 2017-2019, I worked at the same refugee resettlement agency that resettled my family in 1995. There, I witnessed firsthand how similar refugee experiences are — the dreams and fears our families had for us translated across several countries and religions. This made me want to explore all the complicated circumstances that shape a refugee’s life. Some are subtle, like responsibilities that naturally fall on kids because of language barriers, or the long-term effects of trauma when it stays untreated and manifests into everyday behaviors and survival mechanisms.

Although I drew upon my own feelings and experiences with Islamophobia and anti-Arab hate in the school system when writing the book, I was also informed by my experience when working in resettlement. I used to help enroll newly arrived refugee students into their first schools. Unfortunately, many of my students were discriminated against by staff and students alike and often deemed as undesirable in the classroom—especially the teen boys.

There’s this romanticized idea that just because someone has escaped violence that they’re now living happily ever after once they’ve resettled, and while quality of life does truly transform after resettlement, there is often another layer of violence created by xenophobia. We are currently living in a very anti-immigrant and Islamophobic society that continues to shape policies that hurt people and take away lives every single day. Many refugee families are aware of this dichotomy, and tend to tread very carefully for this very reason.

The book is described as being told through multiple points of view across time. How did you choose which voices to include and what were the narrative challenges of moving between perspectives and timelines?

So much trial and error. At first, the book was only going to be about the two boys and their perspectives. But when I began writing, so many voices showed up—parents, siblings, etc. I decided to reel it back and make it about Yassir, Khaled, and Kawther (female MC). But when I got to my fifth draft, I was completing a revise and resubmit for an agent (now representing me), who asked to include a short prologue from the POV of someone we had never met, maybe someone in the community who had witnessed the crime. I played around with a few voices when I realized it wasn’t a human, but the sky itself. This felt perfect since I was struggling with how to explain the multigenerational ties that bonded the boys’ families long before they were born, and Sky allowed for these details to come through naturally as a character who has been quietly watching events unfold for a long time.

Overall, I really discovered everything in layers. It probably wasn’t until draft 4 or 5 that I realized a before/after countdown would really benefit the story. Doing so allowed the story to span farther back than the current day, and allow Kawther’s own coming of age story to be revealed, too.

The story engages with painful family secrets and a devastating crime that reshapes the characters’ lives. What research, conversations, or ethical choices did you undertake to portray those darker elements authentically and sensitively for a YA audience?

A lot of kids are experiencing really dark moments in their lives, and it’s important they have stories where they see themselves in a contemporary, realistic setting and don’t feel alone. My hot take: while I love fantastical stories, I think it’s been disheartening to see the publishing industry push away YA contemporary stories from the market, because there are so many kids of color who have yet to see themselves portrayed realistically. Heavy topics like war, genocide, and injustice are commonly written about in fantasy/sci-fi stories, but they’re often seen as taboo or too heavy in realistic books. I understand these topics are hard to read, but it does a disservice to the realities many of our communities have faced. In a world where there’s so much lack of empathy for other humans, especially as we collectively witness multiple ongoing genocides, I think it’s important that there are stories that do not sugarcoat the real-life circumstances that many of our families experienced only a handful of years ago—or very recently.

As for research, I really just dove into the real things my parents, and other Iraqi parents I grew up around, had experienced. Many were oral stories and random details I’d learned over the years, but there were also various reports I read as well to ensure I stayed as historically accurate as possible. There is an article written by Amnesty International that details the human rights abuses that took place at the refugee camp I was born in, as well as various other reports that detail different war crimes committed against Iraqis during the US invasion in 2003-2007, and real life accounts of torture and mass executions committed by the Saddam Hussein regime. These are all very heavy topics, but they happened, and it’s a reality embedded into most Iraqi lives. So, instead of pretending this violence didn’t exist, I wanted to expose how it affects everyday moments.

However, it’s common for diaspora families, especially those who experienced extreme trauma, to shield their kids from the truth of what happened to them and to carry secrets as a result. I think secrets start as a form of protection. Whether it’s someone protecting themselves or someone else from the truth. Many characters in this book are afraid of facing the truth, and what it would mean to them and their fragile relationships. Because of the multi-gen dynamics in this story, the various ways secrets manifest with different characters felt like a fitting way to explore this common phenomenon among immigrant families.

Your work often celebrates the depth and resilience of SWANA and Muslim identities. How do you see In the Country I Love contributing to the broader conversation about Muslim and immigrant narratives in YA fiction – and what stereotypes or silences did you most want to confront through this story?

I think there’s a lot of pressure to prove that immigrants belong only if they exemplify model behavior, which can be really dehumanizing, unrealistic, and damaging. Many of us believe that if we behave in a certain way, we will belong and be protected from violent rhetoric, stereotypes, or violence. It was important to me that this story shows that this is not true. Of course, there’s good and bad. Not everyone is going to have the same experiences—and I’d hope most Muslims and immigrants do not have to face Islamophobia or xenophobia or both, but it happens more frequently than we like to admit, and instead of shying away from the reality, I wanted to face it head on in the narrative, which is why Yassir and Khaled have such different methods of survival when going to school or dealing with their identities. There is also so much rhetoric that Muslims are the ones who create and administer harm in the US and abroad, when so many of us are the victims of violence, not just individually but in a broader, systemic way. However, this rhetoric is so normalized that I wanted to ensure the crime that takes place in the novel is both loud and centered in the story, yet also a quiet, lingering presence, too.

I also wanted to show how complicated we are. The boys are complex, they’re sensitive, they’re angry, they’re sad, a little funny too—they’re flawed—and it’s because every human is. But they are not always given the same grace as others for their behavior. Western media has portrayed Arab and Muslim males as violent and controlling. I wanted to explore this stereotype in the book, focusing on how characters’ flaws are perceived and why.

I do not wish to prove our humanity to anyone by performing perfect Arab and Muslims characters, but simply to show we’re human, which means we are flawed and complex, just like anyone else. We make mistakes, and we deserve the same dignity to seek forgiveness and love, too.

INTERVIEW: YA SH3LF