Ahmad Saber is a young adult author who grew up on an all-girls college campus next to a massive fort in Pakistan. He now lives in Canada, and loves Broadway (favorite show = Phantom), travel (favorite place = 4-way tie between NYC, Seoul, Paris, and Melbourne), and Taylor Swift (favorite album = folklore) He’s also a self-professed Chocolate Chip Cookie Connoisseur and has crowned New York’s Culture Espresso’s as the best in the world.

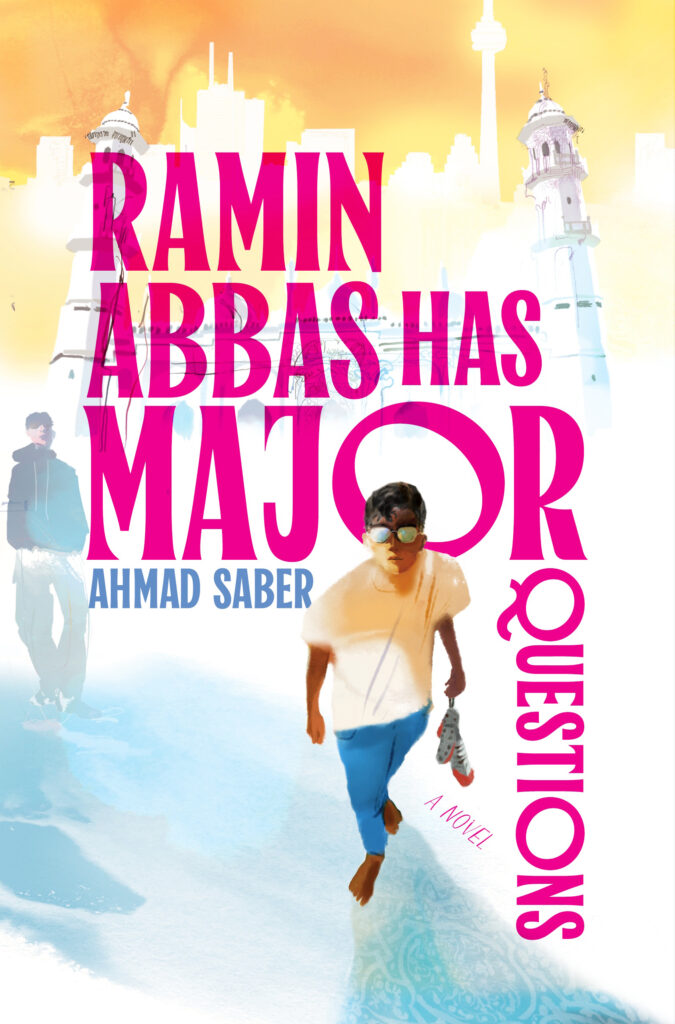

Ramin Abbas has MAJOR Questions is his debut novel and is based in part on his own lived experience, exploring the inherent challenges of being queer and Muslim, and the struggle to reconcile faith with sexuality.

Ahmad is also a medical doctor specializing in rheumatology.

Your book centers on Ramin Abbas, a gay Muslim teen who’s forced to reckon with the tension between his faith and his sexuality. What inspired you to tell this story – and how much of Ramin’s journey draws from your own life or experiences?

The “spark of inspiration” moment came while I was watching a promotional clip of a Muslim high school in North America. I observed the students in the video, happy and joyful, faces lit up with bright smiles, looking like they belonged, like they had found their “tribe.” And then I imagined a closeted teen Muslim boy who’d have to blend into that seemingly-joyful world while having to hide his true, authentic self. I asked myself what kind of internal anguish and suffocation might that kid have to contend with. I’d felt something similar myself while trying to blend into the Muslim Student Association at my college.

Looking further back however, the story had been taking root in my mind long before I recognized the need to write it down on paper. My biggest inspiration was the question I’d asked myself for well over 15 years: is the pain of having to reconcile your sexuality with your religious or cultural identity ultimately meaningless, or could it be given meaning?

Candidly speaking, Ramin began as a self-insert in the very early drafts of the novel but then started to take on a life of his own and ultimately found his own identity, distinct from mine, but with the guiding light of my lived experience. The more I wrote and re-wrote scenes and leaned into his voice, the more I got to know him. By the end, Ramin’s character essentially wrote himself.

Faith, identity, and belonging are deeply entwined in this story. How did you approach writing about religion – a topic that can be deeply personal and sensitive – while also portraying a queer coming-of-age in a Muslim community?

It was a careful and empathy-guided balancing act to write about a queer religious character’s authentic experience in its naked truth, while also purifying my intention not to offend anyone’s religious sentiments. Based on the mainstream and traditional interpretation of Islam’s current stance on homosexuality, there naturally is conflict. However, it was important to remind myself that stories like Ramin’s still need to be told. It’s been far too long that kids like Ramin have endured in silence. My mission with this book is to tell their stories. Not telling them or avoiding the uncomfortable truths won’t change reality. And if, despite the best of my intentions, it offends a fellow person of Muslim faith, I’d like to say to them that this story is one perspective among many, and that it is still possible to have empathy and tolerance for people like Ramin, while exercising the personal freedom of belief and religion.

Ramin’s story involves pressure from family, community expectations, and even blackmail – adding layers of external conflict. What drove you to explore those themes rather than focusing solely on internal conflict or self-acceptance?

Hmm, this very much came down to what I personally like in story-telling! While I’m strongly drawn to character-driven stories and internal conflict, I still like to have that packaged in with some good, old-fashioned drama. Otherwise, there are not-so-unreasonable-odds that I might put the book down or dnf it, even if it’s the most beautiful writing with deep, moving subject matter. I think internal and external conflict are equally important in a good book and plot is definitely among the top 3 most essential elements in books I enjoy (the other two being character and voice.)

Because this is your debut novel, were there particular risks or doubts you faced when writing – especially given the intersection of religion, sexuality, and identity – and how did you decide what parts of the truth you were willing to tackle head-on?

With the current “yoyo” nature of progressive values and the LGBTQ movement, as well as the small but real risk of facing hate and threats, I had to carefully think about if I wanted to put out a book like this out in the world. Eventually, it came back to the mission: to tell stories of kids like Ramin, whose stories haven’t been told enough. I have to admit this is one of the bravest things I’ve done in my life.

I also had doubts about this being a “quiet” book, or “too niche.” However, I was fortunate enough to find an agent and then an editor who “got” the story, truly embraced it, then joined me on the mission to tell it to the world. We have been thrilled to see early signs of the book not being “too niche”, and of resonating with critics! Ramin Abbas has MAJOR Questions is already an Indies Introduce pick for Spring 2026 (by ABA) as well as a JLG gold standard selection.

With regards to the second part of the question, I basically decided to tackle the truth head-on and in the least censored way possible, while letting empathy steer me clear of offending religious sentiment. The truth is, it can be incredibly painful for a queer person to find self-acceptance in a strictly religious Muslim household. I couldn’t find other novels that really went super in-depth on the issue of reconciling faith with sexuality. I hope this book can spark an important dialogue in faith-based communities (even if we’re in the “pullback” phase of the “yoyo” right now.)

Ramin’s experience emphasizes the idea of “which Allah lives in the little mosque in his heart” – a powerful metaphor about faith and inner truth. What does this conflict between traditional expectations and personal truth say about the nature of faith, community, and self-acceptance in your view?

Writing this story and then reading some early reviews re-affirmed for me that faith and sexuality can indeed be reconciled, despite traditional or mainstream interpretations of faith. Faith can either be deeply personal and expression of it almost exclusively internal, or it can be a very outward, shared human experience, in which case, community and belonging can still be found for queer people of faith.

We also have to realize that some queer religious people, even if rejected by their religious families and faith-based communities, may still feel the need to turn to religion for solace and finding inner peace. Similarly, some queer religious people, even if rejected by the “mainstream” queer community, may still feel the need to turn to queer safe spaces on their journey of self-acceptance.

What do you hope readers – especially young people from religious or immigrant backgrounds – take away from Ramin’s story? Are there messages of hope, understanding, or acceptance you want to emphasize most?

For young queer people from religious or immigrant backgrounds, my hope is that you feel seen, and that you realize that despite what people say and how your community may have made you feel, you don’t actually have to choose between your faith and your authentic sexuality.

For all my general readers who may not personally share Ramin’s struggle, my hope is that you can offer a warm hug or lend an empathic ear to someone like Ramin, should you happen to cross paths with them in life. Trust me, they tend to be rather gentle souls!

INTERVIEW: YA SH3LF