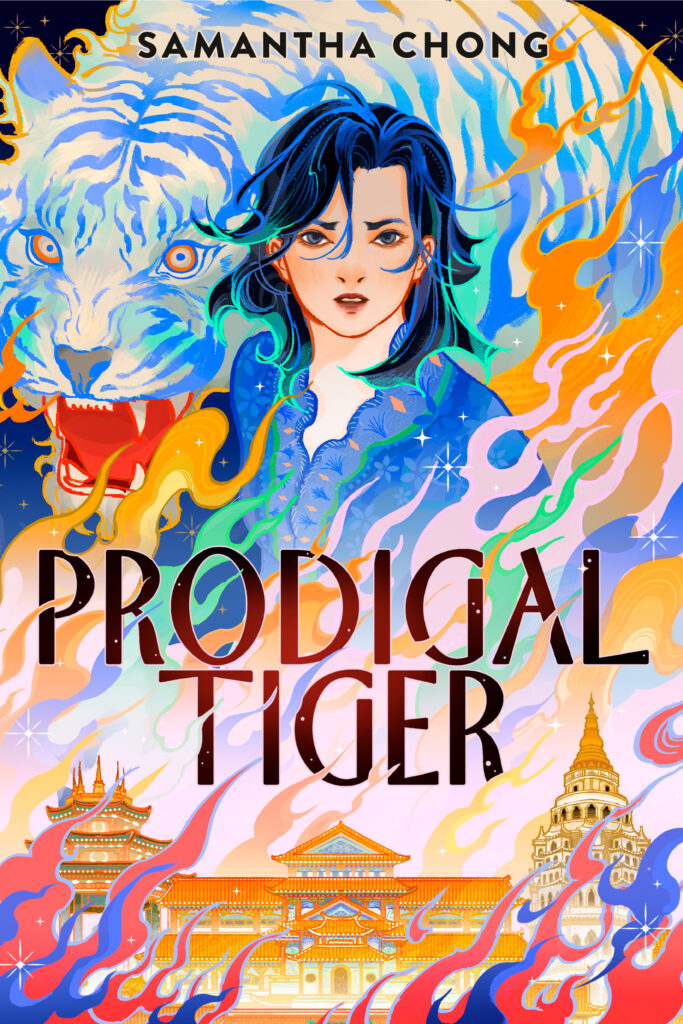

Samantha Chong is a Malaysian-born writer whose work explores identity, belonging, and the pull of home through myth-infused storytelling. Raised in Penang and now based in New York, she draws deeply from Southeast Asian folklore and her own experiences of diaspora. Her debut novel, Prodigal Tiger, is a young adult fantasy that reimagines Malaysian spirits, guardians, and ghosts within a contemporary coming-of-age story, blending cultural specificity with universal emotional stakes. In addition to fiction, Chong is an established cross-platform storyteller, having written travel, culture, and food features for outlets such as BBC Travel, Atlas Obscura, and Gastro Obscura. With Prodigal Tiger, she brings an underrepresented mythology to the forefront of YA literature, marking the arrival of a compelling new literary voice.

Your debut Prodigal Tiger blends contemporary fantasy with vibrant Malaysian folklore, bringing ghostly myths and cultural magic to life. What inspired you to center your story around Malaysian traditions like the Hungry Ghost Festival, and how did you approach adapting those cultural elements into a YA fantasy narrative?

I grew up listening to a lot of ghost stories. I think this is something most Malaysians are familiar with — a lot of my childhood was spent casually hearing things like “Don’t go outside if someone’s calling your name late at night, it’s a pontianak,” or “Don’t stick your chopsticks upright in rice, it looks like incense sticks and may summon evil spirits.” Ghosts are just something that our culture kind of takes as being just there.

So things like the Hungry Ghost Festival always made logical sense to me—like a sense of inevitability, you know? Yes, of course there’s a month in which the dead are free to wander the world of the living, and that’s why we have all of these intricate traditions. That’s just how the world works. When I started writing my book, I knew that I wanted to touch on ghosts encroaching on the world of the living. So the Hungry Ghost Festival naturally surfaced as the flashpoint of the story, since it offered the ghosts a chance to cause some damage.

Knowing that, I dove a bit deeper into the festival, drawing on the stories I grew up with. The Hungry Ghost Festival is a chance to honor your ancestors, and provide for neglected spirits lest they wreak havoc. Which then made me ask myself: What does a neglected spirit wreaking havoc look like, actually? And then the plot, the antagonists, and the worldbuilding kind of spun itself up from there.

I was lucky in a sense because as the plot began developing, I was able to reach into my cultural toolbox and say, Oh, we want to talk about ghosts having an axe to grind? Here’s a cultural explanation for vengeful ghosts. It really lent some weight to the storyline, knowing there was a natural cultural parallel I could draw on, and I think it adds a textural richness to the worldbuilding. I hope readers will be able to catch all the Easter Eggs and winks and nudges.

Caroline’s journey takes her from a magical academy in New York back to her homeland in Penang, where she must confront both supernatural threats and her own sense of belonging. How did your own experiences with global living and cultural identity influence the themes of home, diaspora, and self-discovery in the book?

Like Caroline, I too, left Penang as a teenager and moved abroad. (Unlike Caroline, I did not have to fistfight ghosts for a missing brother—fortunately!)

One thing that struck me when I returned to the island after a few years was how I expected to slide right back into who I was when I left. And when that didn’t happen, I experienced a sense of loneliness, of being shut out of a room I thought I knew all the contours to. It was like the window was frosted over; I couldn’t fully see inside anymore.

My accent was no longer fully Malaysian. I was forgetting words in Malay and Hokkien that I should have known. Locals mistook me for a tourist—a huge insult to me personally! Stores I loved closed. New buildings had risen out of the sea. The island had changed, as had I, which was a little bit of a jarring experience for someone who also felt slightly out of place abroad.

Those early years shaped a lot about how I think about home—about how when you leave a place, it’s never fully yours anymore. There is a saying in Mandarin, 落叶归根, or “falling leaves return to roots”, which means that someone in their old age returns to their hometown. But what happens when the roots sprawl differently, or when the leaves are blown elsewhere by the wind? How does a changing home and a changing sense of self shape how you see the place you grew up? What, then, is home? Is it a place where you grew up, or a place where you grew into yourself? Is it a person? Is it you? Is it your family?

This clash between “what you expect home to be” and “what you want home to be” is part of what made Caroline such an important first character for me. I wanted her to ask herself the same questions about home, especially because she was forced out at such a young age. She, too, is marked as being ‘different’ the moment she steps foot on the island, and she, too, acknowledges how she never quite fit in abroad, either. I drew on a lot of my own complicated feelings to speak through her, and in writing this book and watching her move through this narrative, it’s helped me understand how I see home, too.

Family and legacy play major roles in Prodigal Tiger, especially with Caroline’s mission to save her brother Aaron — who is destined to become Protector of the Island. How did you balance high-stakes supernatural action with the emotional complexity of sibling bonds, expectations, and personal responsibility?

Many, many drafts is the answer, and also a really good editor!

To be honest, the sibling relationship probably changed the most across this book, and that itself affected the way the action was written and rewritten. The very initial Caroline and Aaron dynamic had Caroline being resentful of Aaron’s status as the golden boy, and resenting that she had to return home to save him. But somewhere along the fourth draft, I’d started to realize that the story I wanted to tell wasn’t sibling against sibling. It was more of Caroline confronting the expectations laid upon both her and Aaron (both good and bad) and questioning their worth.

In the end, it really evolved into a story about the narratives that people tell themselves, and about the “legacy” Caroline and her family are both expected to uphold. That theme found its way into so many of the emotional beats scattered across the book—Caroline is constantly asked to confront and challenge the narrative of her being a screw-up. These mindset shifts affect the way she fights and tackles problems, from trying to go it alone to finally admitting she needs help. That itself affects how the action unfolds, and who is asked to go into those fights with her.

To me, the fight scenes are not just there to be fun and flashy. They’re there to underscore some lesson that Caroline needs to learn quickly. Sometimes she does, and sometimes she doesn’t! There are consequences to those fights that spill over into the choices she makes after. Then those choices force her to look at the identity laid at her feet again, and so on, and so forth. In the end, I think that final action sequence is a final test of all the lessons Caroline’s been learning — to defeat the Big Bad, she needs to really figure out who she is, and who she really has in her corner.

The novel features a rich magic system and vengeful spirits with centuries-old grudges. What was your creative process for building this world’s supernatural rules, and were there specific myths, stories, or cultural lore that you drew on or reinvented for this narrative?

A lot of this world’s fantasy rules came from a place of play, where I was discovering the rules along the way. But there were a few things I knew off the bat: the ghosts were generally confined to their own world, with a few exceptions; the tiger was a magical creature only Caroline could wield; all wizards, living and dead, had magic, the only question was where they drew that magic from. I also specifically wanted to pit two forms of magic against each other—internal and external—and draw some parallels between when Caroline uses either of those systems and how they might relate to her own journey of identifying with this place she left behind.

But otherwise, I mostly gave myself room to play, and along the editing process, my brilliant editor helped surface a lot of great questions about the magic system (where do they get it? What is the difference between Caroline’s magic and J.J.’s?, etc). The end result is somewhat of a naturally-flowing magic system, which I like, because it kind of plays on that whole “supernatural things are happening all around us” vibe that I alluded to in the question above. If ghosts are just a normal thing to talk about in Malaysia, then magic can exist in that space too. I quite liked having that flexibility.

We’ve covered hungry ghosts above, so to turn to another cultural touchstone: I knew I would be remiss if I didn’t include the pontianak, who is That Girl when it comes to Malaysian folklore. The pontianak, for anyone unfamiliar, is a female vampiric spirit who is infamous across Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia (she may also be known as the kuntilanak). Said to be the spirits of women who died in childbirth, pontianaks reside in banana trees during the day, and feast on unsuspecting victims during the night.

I grew up with stories of the pontianak, as my mother used to live in some pretty rural villages and passed those stories down to me. Myths she told me about: Never go outside when you hear someone calling your name at night. If you hear a baby crying and it sounds like it’s coming from far away, hurry inside. The smell of frangipani coming from nowhere at night means a pontianak is nearby; run.

As a result, it was a no-brainer to have a pontianak be the first creature Caroline encounters in-text. I wanted a local creature to not only launch us into the thick of action, but also to set the tone and scene for the world readers were about to step into. The pontianak was a lovely cameo, and I’m glad that she has stayed with the opening pages from draft 1 until now — that opening scene has never ever truly changed, which I think speaks to the compelling allure of the pontianak lore!

As a Malaysian author now based in New York City, you bring a unique multicultural perspective to the YA fantasy genre. What do you hope readers — especially those from diaspora or multicultural backgrounds — take away from Prodigal Tiger about the intersections of culture, identity, and belonging?

I’ve recently latched on to the idea of homes being like jackets. You put one on, you take one off. There are some days I feel more Malaysian than American. And I think all of it is valid! You are only on this Earth for so long; you will have inevitably spent more time in some places than others. Even if it’s not necessarily diaspora, even if you moved from San Francisco to Seattle, you will have come face to face with the idea of changing homes. That idea of loss is universal.

Who you are is not necessarily tied to where you grew up, though it can be. I think we really are tapestries of everywhere we’ve ever been; we take places and people with us, letting them shape the edges of who we are. And that’s the heart of Prodigal Tiger, really: it is a story about home, but it is also a story about the choices you make to shape that definition of home.

The idea of home will probably change, because you will change. Any definition you have is a snapshot in time. There’s nothing wrong with that.

This is a journey we are all on together, and this book offers only one answer to the question of home. I look forward to continuing to play in this space. I look forward to hearing what other stories come out of this space. I hope this book is a stepping stone for someone to help them put words to what they’ve been feeling.

INTERVIEW: YA SH3LF